Alain Karsenty, Christian Leclerc et Didier Bazile

Protected areas, instrument of a "green colonialism" in Africa?

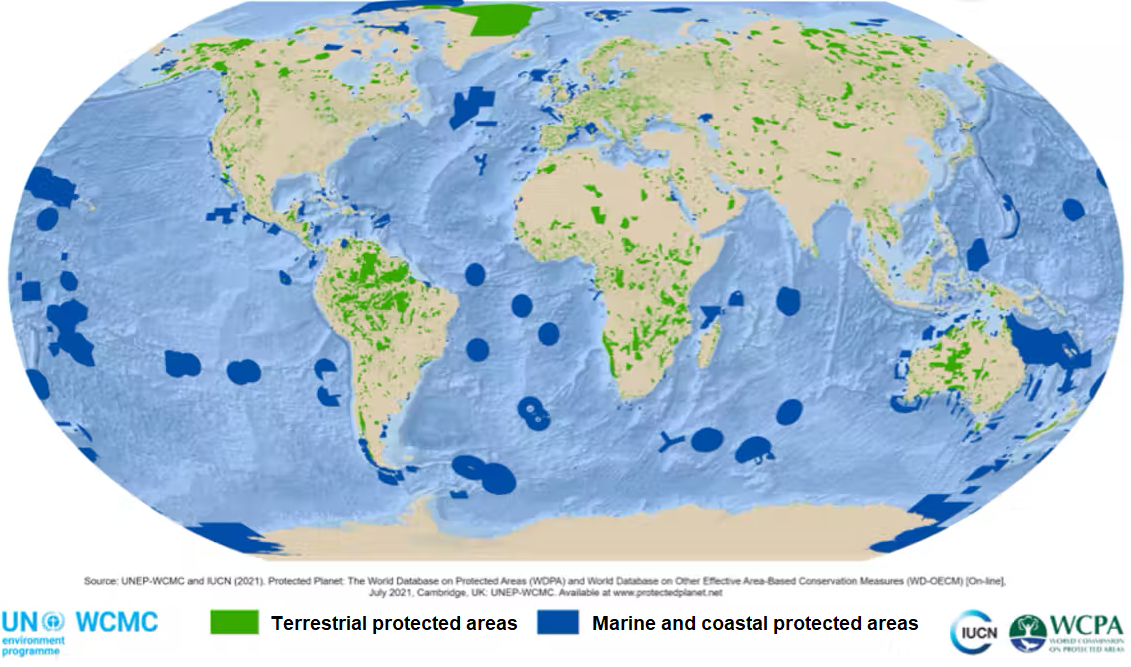

In the context of unprecedented population growth on the African continent, ways to preserve the region’s biodiversity are at the centre of lively debate at the Convention for Biological Diversity – particularly in light of a proposal to classify 30% of national territories as protected areas and with 10% of them to be strictly conserved.

In his 2020 essay, The invention of green colonialism, Guillaume Blanc attacked the IUCN, WWF and UNESCO operating in natural parks in Africa. He accused park managers of excluding and violating local populations, and of creating misery to satisfy a fantasy of virgin nature for the sole benefit of Western tourists. He asserts that:

“This ideal of a nature free of its inhabitants guides the majority of protected areas [emphasis added] on the continent”,

adding that

“National parks do not really protect nature since tourist consumption harms biodiversity”.

- National parks are at the heart of the debate here, and there are two major questions that agitate the conservation community in Africa:

- Is it legitimate to restrict use rights for conservation purposes?

- What model of protected area or alternative strategy for the preservation of biodiversity can reconcile efficiency and consideration of human and land rights?

Nature under multiple pressures

- Pressure on the environment is growing in Africa due to increasing populations in rural areas, which in turn are leading to: increased competition for land and opportunities offered by the world's agricultural demand (cocoa or oil palm), increased charcoal production and urban demand for bushmeat, a rush of artisanal miners for precious stones, and a disparity between the meagre peasant incomes and the commercial value of ivory or rosewood. In addition, some local communities are also being enlisted by poaching networks. In Africa, just as we see in other areas where international demand creates an overexploitation of resources, the majority of the activities undermining biodiversity are carried out by small producers producing for both local and foreign markets.

- The creation of new protected areas remains the domain of African governments, even if certain mechanisms known as “debt-for-nature swaps” (whereby a creditor country reduces the debt of a debtor country) sometimes influence the decisions. But the general picture is not encouraging, with the majority of protected areas in Africa underfunded due to both low tourism revenues and poor management. In addition, revenues from access fees have fallen sharply in recent years with the health crisis. Researchers estimate that between $103 billion and $178 billion is needed to reach the 30% target.

Management increasingly “delegated” to private operators

- Given these financial difficulties, some states are opting to “delegate” the management of parks to specialized NGOs. But faced with the rising power of poaching networks, which are sometimes heavily armed, we also see a parallel trend towards the “militarization” of conservation in certain parks. Acts of violence by eco-guards against populations have been reported in Africa.

- Delegated management often falls to African Parks, a South African NGO accustomed to difficult contexts. But militarization is experienced differently by populations in differing contexts. For example, according to a 2020 survey on the management of Zakouma National Park (Chad), local populations have demanded protection from armed groups seeking to extort them, and they are collaborating with the NGO to report incursions by Sudanese Janjaweed.

- As for effectiveness, several publications show that wildlife resources are better preserved in protected areas that also have high levels of protection. In addition, we must also mention the experiences of community-based conservation, for example Conservancies in Namibia, the Campfire program in Zimbabwe, Village Land Forest Reserves in Tanzania, and some community forests without timber exploitation. These community-based or participatory management areas can be seen as alternatives or complements to strictly protected areas. However, their conservation record is sometimes considered less robust and there is, at least in southern Africa, a tendency to recentralise management under the influence of international NGOs.

- The displacement of populations poses a problem that one must be careful not to give an a priori clear-cut answer. Across the world, expropriation is considered legitimate in order to build infrastructure (roads, dams, etc.), as long as the entitled owners receive adequate financial compensation. However, this entitlement status is a source of contention within protected areas where there are migrants fleeing insecurity or attracted by the land and resources perceived to be available. Customary land rights holders may have accepted or suffered the settlement of these families. The policies of protected area managers towards migrants will vary, ranging from tolerated “cantonment” to outright eviction.

A diversity of tools and approaches for protected areas

- Reducing protected areas to a simple tool for dispossession is to forget the diversity of their status and governance. The IUCN classifies the 200,000 protected areas in the world into six categories:

IUCN

CategoryName

Characteristics and management objectives

Ia

Strict nature reserve

Protected area managed primarily for scientific or wildlife resource protection purposes

(e.g. Swiss National Park, Quebec ecological reserves)

Ib

Wilderness area

Protected area managed primarily for the protection of wild resources

II

National Park

Protected area managed primarily for ecosystem protection and recreational purposes

III

Natural monument

Protected area managed primarily to preserve specific natural features

IV

Habitat or species management area

Protected area managed primarily for conservation purposes, with management intervention

(e.g. the Cap Ferret dunes or the Chambord forest in France)

V

Protected landscape or seascape

Protected area managed mainly for landscape or seascape conservation and recreational purposes

(e.g. Regional Nature Parks in France, Cévennes National Park)

VI

Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources

Protected area managed primarily for the sustainable use of natural ecosystems

(e.g. New Ankeniheny-Zahamena Corridor (CAZ) in Madagascar)

Adapted from IUCN data, provided by the author

Only categories I to III are dedicated to strict conservation, as this is sometimes the only option to protect endangered species. The other categories include economic activities. Category IV is the most common in Africa, and categories V and VI depend on interactions with humans. National parks themselves may be category II, IV, or VI. In addition to these management categories, the governance mode specifies who makes decisions.

|

Modes of governance (according to IUCN) |

|

|

By the government |

Public body, but possibly delegated to an NGO |

|

By individuals and private organisations |

Generally, landowners |

|

By indigenous people and/or local communities |

The community may refer to the population occupying the riparian space of the protected area or living within it in the case of categories V or VI, the population represented by its local elected representatives, or the customary organisation governing access to resources |

Adapted from IUCN data, provided by the author

The last three categories are in the majority, although there are some specificities, for example in South Africa, 57% of protected areas are private – as is often the case with land.

- Protected areas do not therefore aim to “protect an Eden from which man is excluded”. The majority of protected areas created over the last 30 years have integrated human activities. An evaluation of protected area support projects financed between 2000 and 2017 by AFD shows that a dual purpose of conservation and development is always favoured.

- Across the world, only 15% of spaces are protected areas, and many other conservation initiatives exist. If the global objective of 30% is maintained, it would be unrealistic to aim for 30% of “excluding” protected areas at each State level, but rather to consider 30% of areas where the conservation objective frames production activities compatible with a high level of biodiversity preservation.

Do not self-restrict to protected areas

- Concerning this particular 30% CoP15 objective, we should go back to the “other effective area-based conservation measures” (OECM) that CoP14 defined as: “A geographically delimited area, other than a protected area, that is regulated and managed so as to achieve positive and sustainable long-term results for the in-situ conservation of biological diversity (...)”.

IUCN states that: “While protected areas must have a primary conservation objective, this is not necessary for OECMs. OECMs can be managed for many different purposes, but they must result in effective conservation”. For example, a watershed protection policy can lead to effective biodiversity protection. There is a possible compromise, a proposal that was discussed at the CBD but has not yet been acted on: to include OECMs in the 30% target, which would not only make the threshold more acceptable, but also allow it to rise steadily.

- Protected areas alone cannot meet all the challenges posed by the biodiversity crisis. A nationwide reflection that takes into account the interface between different activities is necessary if we are to renew our view of nature and redefine more effective biodiversity conservation strategies.

• Alain Karsenty, Environmental economist, researcher and international consultant, CIRAD

• Christian Leclerc, Ethno-biologist, CIRAD

• Didier Bazile, Researcher specialising in the conservation of agrobiodiversity, biodiversity officer, CIRAD

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article (french).